What Then About Land Expropriation with Compensation? The National Democratic Revolution Must Resolve the Intimately Inter-Connected Land and National Questions!

We recognise and acknowledge the fact that the matter that has been raised of “land expropriation without compensation” has generated a lot of debate throughout our country.

We fully support the determination firmly and effectively to act on the Land Question, among others to redress the injustices of the past, as called for by our National Constitution.

In this context, speaking as members of the ANC, we fully agree with the decision taken at the 54th National Conference of the ANC that such ‘land expropriation without compensation’ should become one of the policy options available to the Democratic Government to address the Land Question.

However, in addition, it is vitally important that the ANC should locate such action within the context of its larger ideological and political perspective, and openly account to the people for all steps it will take in this regard, bearing in mind this perspective.

This pamphlet is intended specifically to explain this ideological and political perspective.

In this context we will firmly underline the view, which derives from this ANC perspective, that this matter of ‘land expropriation without compensation’ is entirely a tactical and operational matter and should not be raised to the level of principle and strategic importance, as has happened!

In this regard we state this openly that the perspective and values we express are of immediate relevance to members and supporters of the ANC, with no assumption or argument that other South Africans are not free to adopt their own different or contrary views.

INTRODUCTION

The decision taken by the 54th National Conference of the ANC in December 2017 on “land expropriation without compensation” has posed important strategic Challenges with regard to many issues which relate to the very character of the ANC. This pamphlet will try to address at least some of these Challenges which are actually of strategic importance to the future of the ANC, the National Democratic Revolution and democratic South Africa.

The reason for this is that the ANC is our country’s governing party, and may continue to play this role for some time to come. Accordingly this makes its views on any issue a matter of national interest.

In this regard it is critically important for all members and supporters of the ANC, as well as all other South Africans, to understand what the ANC actually is, regardless of whatever might have happened during the recent past.

The definition of the character and historic mission of the ANC has been developed and has evolved over a long period of time, starting in the 19th century.

We can summarise this as the development of the extraordinary view that the strategic task of the ANC is to position the peoples of Africa, and specifically the indigenous South African Africans, as frontline fighters for the creation of a non-racial, democratic, humane and humanist global human society.

Accordingly, throughout its years, involving even its antecedents, the ANC has never identified its principal objective as being accession to positions of political power.

Where striving to access such political power became unavoidable because of the 1994 victory of the Democratic Revolution, the ANC has sought to explain that it would use such political power to transform South Africa into the kind of entity we have sought to define.

In essence, responding to the racist, colonial domination of the indigenous African majority which characterised politics and governance in South Africa and virtually the entirety of the rest of Africa as it was formed in 1912, the ANC took exactly the opposition view – i.e. that it stood for the freedom of all humanity, black and white, including the colonial oppressors, and much more besides!

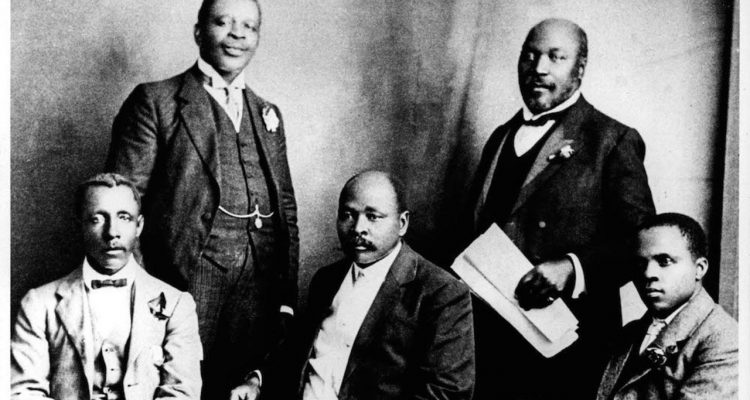

Established in 1912 as a “Parliament of the Black Oppressed”, pursuing the strategic objective we have just stated, the ANC came to be accepted especially by the indigenous African majority as virtually their only true representative and defender of their interests.

Accordingly, successive generations among this indigenous African majority have consistently accepted and treated the ANC as their political home exactly because of how it has defined its historic mission over the decades, and what it has done to accomplish this mission.

What this means is that the view advanced by the ANC, for instance that all South Africans had an obligation to accept that our country had become a multi-racial entity and therefore that it must respect the principle and practice of unity in diversity, became the view of the indigenous majority which had come to accept the ANC as ‘virtually their only true representative and defender of their interests!

Thus such notions as building a “non-racial” South Africa as a central objective of the liberation struggle became a property of the majority of the African oppressed, not merely the ANC.

This is why all political formations which sought to challenge the ANC on this matter of a “non-racial” South Africa failed. This was because the matter to ensure that the successful liberation struggle remained loyal to the task to build a “non-racial” society had become an objective shared by the majority of the African oppressed, regardless of political affiliation.

This was exactly why, accepted as a ‘parliament of the oppressed’, the ANC produced leaders who were accepted by the black oppressed as their true national leaders!

We have advanced the foregoing argument to help explain what the ANC is as well as its standing among the indigenous African majority.

It now remains for us to cite specific examples to illustrate and justify why the ANC, as endorsed by the majority of at least the majority of the indigenous Africans, is a ‘frontline fighter for the creation of a non-racial, democratic, humane and humanist global human society’!

The very founding Constitution of the ANC, adopted in Bloemfontein in January 1912 said that the Objectives of the Native Congress were, among others:

- to promote unity and mutual cooperation between the Government and the Abantu Races of South Africa;

- to promote the educational, social, economic and political elevation of the native people in South Africa;

- to bring about better understanding between the white and black inhabitants of South Africa; and,

- to safeguard the interests of the native inhabitants throughout South Africa by seeking and obtaining redress for any of their just grievances.

Before the adoption of this Constitution, the principal organiser of the Bloemfontein Congress, Pixley Seme had delivered the 1906 speech on the ‘Regeneration of Africa’, and said:

“The regeneration of Africa means that a new and unique civilization is soon to be added to the world. The African is not a proletarian in the world of science and art. He has precious creations of his own, of ivory, of copper and of gold, fine, plated willow-ware and weapons of superior workmanship. Civilization resembles an organic being in its development – it is born, it perishes, and it can propagate itself. More particularly, it resembles a plant, it takes root in the teeming earth, and when the seeds fall in other soils new varieties sprout up. The most essential departure of this new civilization is that it shall be thoroughly spiritual and humanistic – indeed a regeneration moral and eternal!”

Fifty five (55) years later, in 1961, Inkosi Albert Luthuli delivered his Nobel Lecture in Oslo, Norway. Among other things he said:

“Still licking the scars of past wrongs perpetrated on her, could she (Africa) not be magnanimous and practice no revenge? Her hand of friendship scornfully rejected, her pleas for justice and fair play spurned, should she not nonetheless seek to turn enmity into amity? Though robbed of her lands, her independence, and opportunities – this, oddly enough, often in the name of civilization and even Christianity – should she not see her destiny as being that of making a distinctive contribution to human progress and human relationships with a peculiar new Africa flavour enriched by the diversity of cultures she enjoys, thus building on the summits of present human achievement an edifice that would be one of the finest tributes to the genius of man?”

These seminal Statements by Seme and Luthuli, unchallenged and esteemed leaders of the ANC and our liberation struggle during their time and beyond, explain exactly the noble vision of the ANC which made it possible for the great masses of the black oppressed to accept the ANC as their true representative and leader.

This noble vision, which fundamentally challenged imperialism, colonialism and racism, was also communicated in other ANC policy documents.

For example the then President of the ANC, Dr A.B. Xuma, convened a Group of African Leaders in 1943 to comment on the ‘Atlantic Charter’ which had been issued by US President Franklin Roosevelt and UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill, which became the base document for the creation of the United Nations Organisation.

The Group of Leaders established by Dr Xuma as the ‘Atlantic Charter Committee’ produced an historic document entitled ‘The Africans Claims’ which was adopted at the 1943 Annual Conference of the ANC.

In his Introduction to this important document Dr Xuma wrote:

“On behalf of my Committee and the African National Congress I call upon chiefs, ministers of religion, teachers, professional men, men and women of all ranks and classes to organise our people, to close ranks and take their place in this mass liberation movement and struggle, expressed in this Bill of Citizenship Rights until freedom, right and justice are won for all races and colours to the honour and glory of the Union of South Africa whose ideals – freedom, democracy, Christianity and human decency cannot be attained until all races in South Africa participate in them.”

Here the President of the ANC, in the context of a global response to Nazism and the very costly Second World War, once again communicated the historic message of the ANC in favour of ‘freedom, rights and justice enjoyed together by all races and colours’, consistent with the ideological and political posture of the ANC since and before its foundation.

In this context let us also quote from the 1958 Constitution of the ANC, adopted the same year when some of the ANC Members expressed views which led to the formation of the PAC in 1959.

The 1958 Constitution of the ANC stated some of the Objectives of the ANC as being:

- to promote and protect the interests of the African people in all matters affecting them; and

- to strive for the attainment of universal adult suffrage and the creation of a united democratic South Africa on the principles outlined in the Freedom Charter

Thus it is clear that everything we have said in this Introduction speaks about an ANC which has always identified and understood its historic mission as being the heavy task to negate and repudiate the vile racism inherent in imperialism, colonialism and apartheid.

Throughout the century of its existence, while also fully respecting its antecedents, the ANC has therefore done everything to emphasise that it has an historic mission both to help eradicate the legacy of colonialism and apartheid and simultaneously to help create a truly non-racial and non-sexist human society!

It is therefore obvious that the ANC must proceed from this well-established tradition, which identifies it in the eyes of the masses of the black people as their representative and leader, as it takes action to take such action as arises from the adoption by the 54th National Conference of the ANC of the resolution on ‘land expropriation without compensation’.

Whatever such action might be, it can never serve, and must never serve to destroy the noble historic ideological and political positions on the building of united humane societies which the ANC has upheld throughout the years of existence, including as this expresses respect for positions which had been developed by formations among the oppressed which led to the formation of the ANC!

It therefore stands to reason that as far as the ANC is concerned, the Land Question in our country cannot be resolved in any manner which destroys or negates the role of the ANC in terms of helping to create and build the new and humane Africa of which Pixley Seme and Albert Luthuli spoke!

Therefore, among others, the ANC must understand that in the context of the debate about the matter of ‘land expropriation without compensation’, it has an obligation consistently to uphold the two principles:

- South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white; and,

- The land shall be shared among those who work it!

If the ANC abandons these two principled and strategic positions, it must accept that it is turning its back on its historical position as ‘the parliament of the people’ by repudiating views and hopes about the future of our country which the masses of our people have held for many decades, ready to pay any price in their defence!

I

Historically, for more than a century, the international left movement has characterised the progressive struggles for the liberation of colonially oppressed peoples as being national democratic struggles.

Necessarily these would be led by national democratic movements.

This meant that these were struggles to end the oppression of the colonised by the coloniser, and thus, in most instances, to achieve national liberation and independence, affirming the political and international law ‘right of nations to self-determination, up to and including independence’.

That outcome, of practically affirming the right of nations to self-determination, meant that this outcome would resolve or lay the basis for the resolution of ‘the national question’, thus, at least, to free from all national oppression of ‘the nation’ and ‘nationalities’ as might coexist within one country.

Thus one of the tasks of the national democratic revolution is ‘to address the national question’, i.e. the matters we have raised above.

However it is possible both successfully ‘to address the national question’ and, for instance, create a new independent State ruled by a military dictatorship!

This would mean that the masses of the people would have been liberated from domination by the colonial master, but remain dominated by the new domestic authority, the military.

Accordingly, for more than a century, the left movement has insisted that the anti-colonial struggles should result both in the independence of the colonised countries and governance of the newly liberated country by democratic means.

Thus would the anti-colonial struggle result in a true emancipation of the people – such that the people would be freed from colonial domination, as well as, and simultaneously, gain the right to govern themselves, without inheriting the problem of a new, now domestic oppressor!

In brief, the left movement to which we have referred, in its involvement and support for the anti-colonial liberation struggles, has consistently sought to ensure that the extent of the victory of these anti-colonial liberation struggles is measured using two criteria, these being:

- to what extent does the anti-colonial victory represent genuine independence for the formerly colonised, rather than a neo-colonial arrangement; and,

- to what extent is the new independent State governed by the people as a truly democratic entity, committed to serve the interests of the people?

We too, members of the ANC, the Alliance and the Mass Democratic Movement characterise ourselves as a National Democratic Movement, insisting that what has and continues to bind us together as one movement is our common commitment to achieve the objectives of the National Democratic Revolution!

These are contained in the negotiated Constitution of 1996.

They include:

- ensuring that South Africa is a sovereign state;

- building a democratic, non-racist, non-sexist and prosperous South Africa; and,

- addressing the injustices of the past, which have created the very unequal society all South Africans inherited in 1994!

II

The very first and most fundamental historical injustice imposed on the indigenous majority in our country by the Dutch and British colonial regimes and the Settler population – “the original sin” – was the deprivation of that African majority of its sovereignty, independence and freedom.

As South Africans we accept that the direct and immediate consequence of the successful deprivation of that sovereignty was the massive land dispossession of the indigenous people, the black Africans!

In this context, necessarily the National Democratic Revolution would and must mean that it must work to resolve the land question resulting from the process of colonisation, which would also address the Constitutional imperative to address the injustices of the past!

All the preceding suggests that our National Democratic Movement must, of necessity, define some of its historic tasks as being:

- to end the apartheid system, including the phenomenon of white minority rule;

- to ensure that the people of South Africa together have the possibility genuinely to exercise their right to self-determination;

- to ensure that the liberated country governs itself through genuinely meaningful democratic processes; and,

- successfully to attend to the matter of equitable distribution of the land to address an historical colonial injustice.

With regard to the latter, at its December 2017 54th National Conference the ANC adopted a Policy on the land question which, among others, says:

“Expropriation of land without compensation should be among the key mechanisms available to government to give effect to land reform and redistribution.

“In determining the mechanisms of implementation, we must ensure that we do not undermine future investment in the economy, or damage agricultural production and food security. Furthermore, our interventions must not cause harm to other sectors of the economy.”

This was the very first time that the ANC had taken such a position – to expropriate land without compensation – during the 106 years of its existence!

It is therefore important that we say much more than merely report this decision!

Naturally the task ‘to resolve the land question’ through redistribution has been on the agenda of the ANC since its foundation.

III

More recently, to this day, the ANC has recognised the Freedom Charter as the ultimate guide in terms of policy formation which, naturally, would take into account the changed conditions since the Charter was adopted in 1955, 63 years ago this year.

It is therefore important to recall what the Freedom Charter says on the land question. It says:

“The land shall be shared among those who work it!

“Restrictions on land ownership on a racial basis shall be ended, and all the land re-divided among those who work it, to banish famine and land hunger. The state shall help the peasants with implements, seed, tractors and dams to save the soil and assist the tillers…”

Here the objectives of land redistribution are specific and clearly stated. They are to:

- achieve equitable ownership of land among those who actually use the land to farm productively;

- use such redistribution to end land hunger;

- use this redistribution to end famine/nutritional shortfalls; and,

- enable the democratic State to intervene to help the tillers who would have acquired land because of the redistribution to become successful farmers while addressing environmental matters concerning the land.

With regard to the foregoing it is clear that when the Freedom Charter stated 63 years ago that ‘land shall be shared among those who work it’, this was based on proposals made by the people, which the national democratic movement adopted, based on the understanding that:

- there were large numbers of people among the oppressed, especially those in the rural areas, described in the Freedom Charter as peasants, who wanted access to land to use it for productive purposes;

- such access to land by these ‘peasants’ would help to eradicate the serious national problem of poverty, which also manifested itself as malnourishment/famine among millions of people; and,

- an important part of the process of the creation of a non-racial society, to give meaning to the objective stated in the Freedom Charter as ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’ would be the intervention of the State to ensure the emergence in democratic South Africa of a numerically and economically significant group of successful black small land holders, but not necessarily a few large successful commercial black tillers of the land. Both black and white ‘tillers of the land’ would exist side-by-side sharing the land as tillers!

In the years since the Freedom Charter was adopted, especially during the years immediately preceding the victory of the Democratic Revolution in 1994, the ANC adopted more detailed positions on ‘the land question’, all of which reiterated the imperative to effect land redistribution.

We refer here especially to the following Policy Documents:

- Policy on the Restitution of Land Rights adopted in 1991;

- Ready to Govern: ANC policy guidelines for a Democratic South Africa also adopted in 1991; and,

- The Reconstruction and Development Programme adopted in 1994.

As we would expect, even as they made more detailed comments about ‘the land question’, these Documents kept broadly within the parameters set by the Freedom Charter.

Given that these Documents were prepared in conditions when our country was progressing towards the victory of the Democratic Revolution, and therefore an end to the centuries-old system of white minority domination, they had to make more detailed proposals towards the resolution of ‘the land question’ to guide the interventions of the forthcoming democratic State.

In this context, and correctly, they also brought into consideration of ‘the land question’ the important matter of urban land, whereas the Freedom Charter essentially focused on rural land, except as it addressed such matters as urban housing, the abolition of ghettoes and slums and urban infrastructure.

Similarly, and correctly, they also raised important issues about the usage, etc, of the communal land in the ‘Native Reserves/Bantustans’, as did the Freedom Charter.

Without citing many extracts from the ANC Policy Documents referred to above, the reality is that, as we have said, they accepted and were informed by the broad framework that had been set by the Freedom Charter.

IV

Thus, until December 2017, the ANC had, for 105 years, adopted the position on ‘the land question’ which was codified in the Freedom Charter.

Central to that historic position of our liberation movement were the principled propositions that:

- the historical injustice of the colonial process of land dispossession had to be addressed, through a purposeful process of land redistribution, some of which land could be acquired by the democratic State through expropriation;

- this would be done to address specific challenges, including satisfying land hunger, contributing to the eradication of poverty, and achieving development; and,

- because of its impact in terms of wealth-creation and distribution and employment-creation, the land was central to the process to reduce the prevalent and enormous racial and gender inequality in our country in terms of wealth and income distribution.

Throughout the evolution of this policy, over 105 years, which has most often included land expropriation, there had never been any decision by the National Democratic Movement until December 2017 that such land expropriation as might be necessary would exclude compensation.

Indeed the document “Ready to Govern…” specifically addresses this matter of compensation and says:

“In establishing an equitable balance between the legitimate interests of present title holders and the legitimate needs of those without land and shelter, compensation by the state in the national interest will have an important role to play. It will be unjust to place the whole burden of the cost of transformation on the shoulders either of the present generation of title holders or on the new generation of owners. The state therefore must shoulder the burden of compensating expropriated title holders where necessary and subject to the provisions in the Bill of Rights. At the same time attention must be given to ensuring that appropriate compensation or other acknowledgement of injury done, shall be given to victims of forced removals and other forms of dispossession.”

We draw attention to the fact that the immediate preceding paragraph authorises both land expropriation and compensation of those expropriated “where necessary” and “subject to the provisions in the (Constitutional) Bill of Rights”!

This was the official ANC policy position which informed the engagement of the ANC representatives in the Constitutional Assembly in the post-1994 constitution-making process.

It is obvious that as the 54th ANC National Conference discussed the Land Resolution, the delegates understood that with regard to the proposal to expropriate land without compensation they were going outside of and beyond then existing ANC policy, hence the heated and fractious debate which ensued at the Conference.

In this regard it is important to recall that this matter had been discussed at the July 2017 ANC Policy Conference. With regard to Land Redistribution the Report of this July 2017 Policy Conference said, among other things:

“A radical land redistribution process is needed to correct South Africa’s unjust and racially skewed ownership patterns, which are based on a long history of colonial dispossession and white domination that is yet to be reversed. This programme must be directly linked to the radical social and economic transformation objectives of increased employment creation, and reduced poverty and inequality particularly in rural areas.

“Government’s approach to land reform is based on three pillars: tenure for farmworkers, restitution, and redistribution. The programme of land redistribution has been inadequate. Not enough productive land has been transferred into the hands of black farmers and producers. Support programmes for new farmers have also been ineffective

“The Expropriation Bill that is before Parliament should be finalised during the course of this year in order to provide impetus to the land reform process.

“The Commission looked at the best means to achieve a more radical programme of accelerated land reform. Two approaches were identified:

“a. Option 1: The one view in both commissions was that the Constitution should be amended to allow the state to expropriate land without compensation.

“b. Option 2: Others were of the view that the s25 of the Constitution did not present a significant obstacle to radical land reform, and that the state should act more aggressively to expropriate land in line with the Mangaung resolution, based on the Constitution’s requirement of just and equitable compensation.

“The ANC must develop a set of proposals that radicalize the redistribution programme to restore land to the people without placing an undue financial burden on the state. In pursuit of these objectives all options should be on table including legislative, constitutional and tax reforms and a set of concrete proposals should be presented to the 54th National Conference of the ANC.”

The July 2017 ANC Policy Conference visualised ‘a radical redistribution programme to restore land to the people without placing an undue burden on the state’.

It stated that such land redistribution would have to be ‘directly linked to the objectives of increased employment creation, and reduced poverty and inequality particularly in rural areas’.

As we have said, the December 2017 ANC National Conference opted for what was described in the ANC Report of the July 2017 Policy Conference as Option 1, which Option was not adopted by the July Policy Conference.

The decision of the Policy Conference was consistent with the historic position of the ANC.

This was that the Movement insisted on the absolute imperative to address the Land Question, and therefore ensure the necessary land redistribution. Nevertheless the Movement also insisted on a synchronised resolution of the related Land and National Questions.

Accordingly, during its 105 years the ANC had never put forward the proposal adopted at the December 2017 ANC National Conference of ‘land expropriation without compensation’.

V

However, unfortunately and strangely, the published ANC Land Resolution as adopted at the December 2017 54th National Conference contains no explanation as to why the ANC felt it necessary to effect such important policy change as was intended by prescribing a general principle of ‘land expropriation without compensation’!

We have therefore had to depend for this explanation on public speeches made by the leaders and representatives of the ANC.

The argument these have advanced to explain why it was necessary to adopt the particular section of the Land Resolution we are discussing is that:

‘The European settlers who colonised our country expropriated the land they came to own from the indigenous people using force and without paying any compensation. Accordingly the ownership of the land by the descendants of these settlers is illegitimate. To correct this historical injustice it is necessary to reverse what happened during the process of colonisation, including the apartheid era, by expropriating this very same land without compensation and returning it to the formerly dispossessed, the Africans! During the implementation of this policy, care must be taken not to discourage investment in the economy, to make a negative impact on agricultural production, etc.’

Understood literally, this explanation means that the ANC formally adopted a policy which said that it was correct, “to address an historical injustice”, to expropriate without compensation one national group for the benefit of another national group!

[We use the category of “national group” in the sense in which it was used in the Freedom Charter.]

With regard to this matter, and in the context of the history of our national liberation struggle, it is impossible not to recall the circumstances of the formation of the PAC in 1959!

A central issue which led some members of the ANC at the time to break away and form the PAC was their objection to the idea stated in the Freedom Charter in these words – ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’, as well as everything else which derived from this principle.

This break-away group considered this a betrayal of the national liberation struggle and countered with the slogan – Africa for the Africans!

However the ANC and the broad democratic movement defended the positions stated in the Freedom Charter as the correct and progressive posture to take in the context of our national reality.

That this was part of a continuing challenge that related to the very character of our liberation movement was confirmed by some developments just over a decade after the PAC breakaway.

These involved the occurrence of another breakaway after the 1969 Morogoro Conference when there emerged within the ANC ranks in exile a group which ended up being called “the Gang of Eight”.

This Gang of Eight formed itself into a faction and put forward more or less the same positions as had been advanced by the PAC.

Efforts by the ANC leadership over something like two years to engage this group to persuade it to return to the established policies of the ANC, including involving comrades from the other national groups in senior structures of the ANC, short of the NEC, failed.

The Gang of Eight was subsequently expelled from the ANC early in the 1970s.

In the context of the immediate foregoing, we would argue that it was necessary for the ANC openly to explain the matter of ‘land expropriation without compensation’ relative to the fundamentally important position adopted by our Movement since its foundation that, as stated in the Freedom Charter, ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’!

VI

This principled position is an important part of what, in our country, must constitute the progressive ‘resolution of the National Question’!

Ours is essentially the only formerly colonised African country where millions of the descendants of the former Colonial Settlers remained as resident citizens after the country’s liberation from colonial and apartheid) rule.

Of the African countries, colonial Algeria had the second largest Settler population after South Africa. At independence in 1962, this settler population amounted to 1.6 million persons, the overwhelming majority being French. This entire Settler population left Algeria after the country’s independence!

Accordingly there was no need for the Algerian national liberation movement, led and represented by the FLN, to consider how the indigenous Algerians should coexist with what had been a Colonial Settler population. In essence the end of French colonial rule meant ‘the resolution of the national question’ as this concerned the relations between the indigenous Algerian population and the French colonial settlers.

To the contrary, in our case ‘the resolution of the national question’ necessarily meant and means that the National Democratic Movement had to ensure that:

- the (colonially) black oppressed, the dominated under apartheid white minority rule, were liberated from such oppression; and,

- the matter of the relations between this formerly oppressed black majority and the erstwhile oppressor white minority is addressed.

With regard to the latter, the ANC could have adopted a position which could have said:

‘The white settlers came to our country uninvited by the indigenous people and are here by virtue of the military conquest of our country. The continued stay of their descendants is therefore illegitimate. They must therefore return to where they came from. Those who stay must know that they do so at our pleasure and as guests!’

A dramatic expression of this approach was exemplified, for instance, by the then PAC slogan – ‘One settler, one bullet!’

VII

In December 1960 the journal ‘Fighting Talk Vol 14, No 7’ published an article by the now late and well known Professor Jack Simons entitled “The Pan-Africanists”.

Among other things Jack Simons drew from different speeches made by PAC representatives “to convey the general tone” of these speeches. Prof Simons used these speeches to elaborate this composite policy statement which communicated the views of the PAC at that time:

“There is no room for Europeans in Africa. We do not want to chase whites away from here. If we chase them away from here we will have no servants. Their wives will work for our wives. The days of the Whites are numbered. We shall apply Section 10 to them. If the Whites accept Africanism, that is good. Let them stay. If not, they must pack up and go. If any European or Coloured wants to join us he must first see the native commissioner and declare himself as a native and pay the £1.15s tax. Let him rub out his name as a European. The Coloured or European can join the PAC providing that he admits that he is an African not a European.”

Bear in mind that with regard to this matter, which related to the post-apartheid relations between the black indigenous majority and the descendants of the original Settler population, the ANC and the rest of the Congress Movement had already taken the positions that, as expressed in the Freedom Charter:

“South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white;…our people have been robbed of their birthright to land, liberty and peace by a form of government founded on injustice and inequality;…our country will never be prosperous or free until all our people live in brotherhood, enjoying equal rights and opportunities;…only a democratic state, based on the will of all the people, can secure to all their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or belief;…we, the people of South Africa, black and white together, equals, countrymen and brothers adopt this Freedom Charter;… and,

“All National Groups shall have equal rights;…all national groups shall be protected by law against insults to their race and national pride;…the preaching and practice of national, race or colour discrimination and contempt shall be a punishable crime; all apartheid laws and practices shall be set aside.”

The March 1961 edition of ‘Fighting Talk Vol 15, No 2’ carried a response to the earlier article by Jack Simons we have cited.

Entitled “Looking for Allies is a Slave Habit”, it was written by a PAC representative who signed him/herself “Terra”, and said, inter alia:

“(The ANC) deceived the Africans by saying it was going to divide the land equally among the workers and not amongst Africans; deliberately the ANC preached a warped form of nationalism christened “progressive nationalism” and not African nationalism.”

Over two years earlier, the November 1958 edition of ‘Contact Vol 1, No 20’, the Liberal Party journal, had published comments of one of the leaders of the PAC, the late Potlako Leballo, who took the place of Robert Sobukwe when the latter was imprisoned. Potlako Leballo said:

“The African people in general do not want to be allied with the [white] Congress of Democrats. They know these people to be leftists and when we want to fight for our rights these people weaken us… We also oppose the ANC’s adherence to the Freedom Charter. The Charter is a foreign ideology not based on African nationalism.”

The same ‘Contact Vol 1, No 20’ of December 1958 published comments made by the late Duma Nokwe, then Assistant Secretary General of the ANC, and said:

“One of the chief arguments of the Africanists is that the ANC has not adhered to its 1949 Programme of Action. But this Programme is merely a set of activities. It lays down no policy whatsoever…The programme does not define the content of African nationalism. It does not say that the brand of African nationalism to be followed is narrow, racialistic and chauvinistic. And the content which has been developed through the years is the progressive African nationalism which is in fact the policy of the ANC today…embodied in the Freedom Charter.”

In this regard the document on Strategy and Tactics adopted at the ANC Morogoro Consultative Conference in 1969 said:

“Our nationalism must not be confused with the chauvinism or narrow nationalism of a previous epoch. It must not be confused with the classical drive by an elitist group among the oppressed people to gain ascendency so that they can replace the oppressor in the exploitation of the mass. But none of this detracts from the basically national context of our liberation drive. In the last resort it is only the success of the national democratic revolution which — by destroying the existing social and economic relationships — will bring with it a correction of the historical injustices perpetrated against the indigenous majority and thus lay the basis for a new — and deeper internationalist — approach.”

It was exactly to express this “progressive African nationalism”, against a “narrow, racialistic and chauvinistic nationalism” that the ANC and the rest of the Congress Movement adopted the positions on ‘the resolution of the national question’ contained in the Freedom Charter paragraphs we have cited.

Among others, the 1969 Morogoro Conference also discussed the ‘land question’. The decision it adopted stated in part:

“The Africans have always maintained their right to the country and the land as a traditional birthright of which they have been robbed. The ANC slogan “Mayibuye i-Afrika” was and is precisely a demand for the return of the land of Africa to its indigenous inhabitants. At the same time the liberation movement recognises that other oppressed people deprived of land live in South Africa. The white people who now monopolise the land have made South Africa their home and are historically part of the South African population and as such entitled to land. This made it perfectly correct to demand that the land be shared among those who work it… Restrictions of land ownership on a racial basis shall be ended and all land shall be open to ownership and use to all people, irrespective of race.”

VIII

It was with regard to this context that statements made by the leadership of the ANC after the December 2017 54th National Conference, that land would be expropriated from one national group, without compensation, and handed to another national group, came across as representing a radical departure from policies faithfully sustained by the ANC during 105 years of its existence!

This was a radical departure not because of either the notion of ‘expropriation’ or the adoption of the concept of ‘without compensation’!

It was a radical departure for an entirely different reason.

That reason has to do with the extremely fundamental question of the very definition of the nature, character and objectives of the National Democratic Movement in our country, as led by the ANC!

As explained by the leaders of the ANC, the policy of land expropriation without compensation means that we should, for instance, now say:

‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, except as this relates to land; and,

‘All national groups are equal before the law, except as this concerns land!’

In other words, the victorious National Democratic Revolution must define the constituencies it serves within a context of ‘winners and losers’ among our country’s national groups.

This would be based on the thesis that ‘for these, the erstwhile oppressed who were losers, it is strategic that the democratic State intervenes to ensure that the erstwhile oppressors lose, to make it possible for the formerly oppressed to succeed’!

Put simply and directly, the decision taken by the ANC at its December 2017 54th National Conference on ‘the Land Question’ raises the question – whom does the contemporary ANC represent, given its radical departure from historic positions of the ANC on ‘the resolution of the National Question’!

It may very well be that that the ANC leadership is perfectly capable of answering this question in a satisfactory manner.

IX

This very same question arises because through its 54h National Conference decision on our country’s historic ‘the Land Question’, the ANC has presented the people of South Africa, black and white, with a challenge very new to our National Democratic Movement, which they have therefore never had to confront and consider.

The 54th National Conference of the ANC adopted a Resolution on ‘the Land Question’ which:

- prescribed that the resolution of ‘the Land Question’ must be based on correcting the outcomes of the armed colonial conquest and land dispossession which occurred in the period encompassing the period from the 17th to the 20th centuries;

- decided that with regard to the matter of the land, it would divide the South African population into two Sections, these being:

(i) the white descendants of the colonists of the emigrant Europeans who settled in our country from 1652 to date, and,

(ii) the original African population which had occupied particular territories since and even before 1652; and,

- would redistribute the land through expropriating without compensation of those defined under (i) above for the direct benefit of those defined under (ii) above!

At the centre of the argument to justify this entirely new approach of the National Democratic Movement, including the ANC, is the assertion that:

- as part of its strategic task to address ‘the National Question’, it is imperative that the National Democratic Movement must address the challenge posed by the fact that one of the distinguishing features of the process of colonisation was the land dispossession of the indigenous majority!;

- as much as the colonial land dispossession process meant land expropriation without compensation, so must the National Democratic Revolution respond by effecting land expropriation without compensation; and,

- the victorious National Democratic Revolution must define the constituencies it serves within a context of ‘winners and losers’, based on the thesis that ‘for these, the erstwhile oppressed who were losers’, it is strategic that the democratic State intervenes to ensure that ‘the erstwhile oppressors lose, to make it possible for the formerly oppressed to succeed’!

It is only in this context that there can be any meaning to the December 2017 Resolution of the 54th ANC National Conference which talks today exclusively and only about land redistribution in historical and racial terms, with absolutely no reference to the important class elements of this matter, among others!

X

By definition political revolutions are about a decisive transfer of power from one social formation to another.

It must therefore stand to reason that the political victory of our own National Democratic Revolution meant such a transfer of power.

Our NDR did indeed address this question, to discuss the transition from apartheid to democracy, and based on the historic statement contained in the Freedom Charter, stating that – The people shall govern!

Correctly, the ANC has been asserting that it has historically acted as a representative of the people of South Africa, black and white, and is currently working to correct past mistakes so that it can, once again, legitimately and practically, re-occupy this position.

At the same time, the position the ANC has taken in the context of ‘the land question’ raises important questions about exactly this matter – which is the matter of the very strategic definition of the ANC as a representative of the people of South Africa!

Certainly, the argument that has been advanced by the ANC leadership since the 54th National Conference about the Land Question communicates the firm statement that the ANC has changed in terms of its character. It is no longer a representative of the people of South Africa.

Rather, as its former President, Jacob Zuma, said, it is a black party!

In this regard, as reported by the newspaper, City Press, when ANC President Zuma addressed the National House of Traditional Leaders on March 3, 2017 he called on “black parties”, including the ANC, to unite to get the two-thirds majority to amend the Constitution to allow for land expropriation without compensation!

Earlier, when he addressed Parliament in February 2017, Zuma had said:

“Historically disadvantaged people must unite on these matters so that we have sufficient majority in Parliament to take these decisions…We must use our majority to correct the wrongs of this country within the law and within the Constitution…The time has come that all of us should unite, speak in one voice…No one will help us but ourselves.”

Jacob Zuma was advancing a perspective about ‘the resolution of the National Question’ radically different from the long established an historic position of the ANC, which he led at the time.

As part of this, he also made bold to change the very nature of the ANC, characterising it as a “black party”.

It might be that at that time many in the ANC did not understand that what Zuma was advancing was, in fact, a fundamental redefinition of both what the ANC is and its historic mission.

Further to clarify his mission, during 2018, even after he had left Government, Jacob Zuma said that South Africa should no longer be a ‘constitutional democracy’ but must become a ‘parliamentary democracy’!

In this regard Zuma was returning to what he had said in February 2017 that the ‘black Parliamentary majority’must have the freedom to determine the future of our country with none of the constraints imposed by our Constitution!

It is very obvious that this Zuma position fundamentally repudiates the historic positions of the ANC not only on the National Question, but also on the matter of the protection of the masses of our people by putting in place Constitutional guarantees and mechanisms which protect these ordinary people, and therefore the very weak, from abuse by powerful holders of political power!

By seeking to remove Constitutional power and restraint, Zuma seeks to assert the possibility for mere parliamentary majorities to be abused as legitimising authoritarian rule by any party which would gain a parliamentary majority, including as this would have been achieved through corrupt means.

XI

To return specifically to the matter of issues generated by the decision of the 54th ANC National Conference on the Land Question, the former member and leader of the ANC, and current leader of the Congress of the People (COPE), Mosioua Lekota, publicly posed an appropriate question after that Conference.

He asked – given that the ANC had resolved to expropriate land and transfer it to those the ANC described as ‘our people’ – who in this equation were not ‘our people’ in terms of long established ANC policy?

The truth is that the ANC leadership has not answered this very legitimate question, except through heckling Lekota to silence him.

In this context we must state that in reality the 54th National Conference of the ANC accepted the leadership of the EFF on this matter when it adopted its resolution of the Land Question!

It is therefore very interesting that whereas the ANC leadership seemed incapable of answering the question posed by Mosioua Lekota, the leader of the EFF, Julius Malema, made bold publicly to answer this question.

At the National Assembly in February 2018, Malema responded to Lekota and said:

“You can’t ask – who are your people? – because the National Democratic Revolution answers that question. It says the motive forces which stand to benefit from the victories of this Revolution – those are our people. The motive forces of the National Democratic Revolution which you went to prison for – the motive forces of the National Democratic Revolution are the oppressed, the blacks in general and the Africans in particular.”

It is therefore very plain that what the EFF considers to constitute ‘our people’ with regard to the Land Question are ‘the blacks in general and the Africans in particular’!

Obviously this means that those who are not ‘our people’, according to the EFF, whose land must be expropriated without compensation, are the white sections of our population!

The EFF position concerning the matter of who ‘our people’ are, as explained by Julius Malema as quoted above, is of course a vulgar and gross misrepresentation of the historic positions of the ANC on the National Question.

Nowhere in any of the policy documents of the ANC since our liberation, including the documents on Strategy and Tactics as adopted at the ANC national Conferences, has the Movement departed from the basic positions on the National Question as stated in the Freedom Charter.

XII

Obviously Malema and probably others in the EFF have not been exposed to such ANC documents as the 1996 Discussion Document entitled “The State and Social Transformation” – hence the patently evident failure to understand the tasks of the democratic State to the people as a whole.

In this regard, as an example, the document “The State and Social Transformation” says, among other things:

“It is the task of this democratic State to champion the cause of (the majority who have been disadvantaged by the many decades of undemocratic rule) in such a way that the most basic aspirations of this majority assume the status of hegemony which informs and guides policy and practice of all the institutions of Government and State. However, there is a need to recognise that the South African democratic State also has the responsibility to attend to the concerns of the rest of the population which is not part of the majority defined above. To the extent that the democratic State is objectively interested in a stable democracy, so it cannot avoid the responsibility to ensure the establishment of a social order concerned with the genuine interests of the people as a whole, regardless of the racial, national, gender and class differentiation. There can be no stable democracy unless the democratic State attends to the concerns of the people as a whole and takes responsibility for the evolution of the new society.”

Thus, contrary to what Malema argued about the democratic State having a responsibility only to ‘the motive forces of the national democratic revolution, and therefore the blacks in general and the Africans in particular’, the preceding paragraph from a 22-year-old ANC Discussion Document explains the actual positions of the ANC on the National Question after the victory of the Democratic Revolution.

What is said in this paragraph represents what Duma Nokwe characterised 60 years ago, in 1958, as “the progressive African nationalism which is in fact the policy of the ANC today…embodied in the Freedom Charter”, as opposed to what he described as “the brand of African nationalism…(that) is narrow, racialistic and chauvinistic”.

However, the challenge that now faces the ANC is that the Resolution on the Land Question it adopted at its 54th National Conference, which, as explained by the leaders of the ANC pursues exactly the positions advanced by the EFF, and therefore does precisely what Malema argued for – that the white section of our population should be excluded from the definition ‘our people’, reserving it for ‘the blacks in general and the Africans in particular’!

The ANC leadership in particular has an obligation to explain to the masses of the people of South Africa:

- when the ANC decided to change its fundamental position on the National Question;

- what reasons have been advanced to explain and justify this change;

- how this change relates to the principle and practice that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white; and,

- what the regression of the ANC on the National Question to positions advanced in 1958 by what became the PAC means in terms of the policies and programmes of the democratic State.

As we said earlier in this document, the resolution of the Land Question has always been one of the important elements on what the ANC described as the Agenda of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR).

In this regard the ANC has always recognised the fact that the process of colonisation in our country has also meant and resulted in the vast land dispossession of the indigenous African majority.

Accordingly, and obviously, one of the tasks of the NDR would be to address the Land Question to ensure equitable access to the land, in a manner which also addresses the historic grievance among the black majority about the colonial and racist process of land dispossession.

XIII

As we indicated earlier in this document, the Freedom Charter provided the principal guidelines for what the victorious National Democratic Movement should do about both rural and urban land.

As we all know, with regard to agricultural land, the Freedom Charter said that – The Land Shall be Shared Among Those Who Work It!

Under the theme – There Shall be Houses, Security and Comfort! – the Freedom Charter listed objectives which address the matter of urban land.

It is correct that the ANC should have been challenged publicly, as has happened, concerning what it has done about the Land Question after more than twenty (20) years as the Governing Party.

It would have been important that the ANC responds to this challenge honestly and with all due seriousness, given the importance of the issue.

Accordingly the ANC would have had to engage in a serious Internal Review process of what it had done to address the Land Question.

In this context it would presumably have agreed that:

Land is required for different purposes, these being:

(i) agricultural production;

(ii) urban housing and human settlements;

(iii) location of commercial enterprises;

(iv) recreation and National Parks;

(v) location of Government and State institutions;

(vi) location of public service institutions;

(vii) environmental objectives; and,

(viii) settling historic land claims as defined by law.

Having made this determination, the ANC would then have to make an assessment as to what needed to be done in each and all these categories to address the Land Question as understood in the context of the NDR.

Thus the Internal Review would pose to itself such questions as:

(ix) how many of the formerly oppressed want to be farmers, and therefore how much land should be acquired to meet such land hunger;

(x) how much urban land should be acquired, among others to change the spatial requirements to end the pattern of the apartheid human settlements;

(xi) what land should be set aside, and where, to facilitate the establishment by the formerly oppressed and other investors of their commercial enterprises;

and so on.

As a result of such an Internal Review, various questions would arise, such as:

(xii) how many people among the formerly oppressed actually want to become tillers of the land, both as active farm owners and farm workers;

(xiii) how many among the formerly oppressed need urban land for purposes of building their own houses and establishing their own communities;

(xiv) how many among the formerly oppressed need land to establish their own enterprises;

(xv) in essence what is the extent of ‘land hunger’ among the formerly oppressed, and for which land use does this ‘hunger’ yearn?

The Internal Review would have considered all the matters we have raised above bearing in mind that access to land and its use in our country must be considered in the context of addressing other important national objectives such as:

(xvi) increasing agricultural production to ensure food security;

(xvii) using agriculture significantly to reduce especially rural poverty and unemployment;

(xviii) using agriculture to achieve women’s development and empowerment in the rural areas; and,

(xix) ensuring the modernisation of agriculture using modern technologies, which require much less land for some crops and provide for radically reduced volumes of water.

Again taking into account all the preceding, the Internal Review would have had to consider the impact on the implementation of NDR policies on the Land Question of such global social tendencies, which also manifest themselves in South Africa; as:

(xx) the historic process of rural-urban migration which empties rural areas of people and very often concentrates significant sections of the population in urban slums;

(xxi) the reduction of the share of agriculture in the Gross Domestic Product, making Agriculture a very small player in terms of national wealth creation, with this figure currently being between 2% and 3%;

(xxii) the fact therefore that the citizens will continue to look for jobs in the other sectors which contribute much more to the GDP, all of which are urban based; and,

(xxiii) the reality that nevertheless agriculture remains important because of essentially four reasons, which are that (a) our country needs an agricultural sector which guarantees our food security, (b) despite the important technological advances in production methods, agriculture continues to be a major employer in terms of the rural population, (c) agriculture produces important raw materials for various industrial processes, and (d) agriculture produces commodities which are important in terms of our exports and therefore foreign exchange earnings.

What we are arguing is that it was and remains necessary for the ANC to undertake the Internal Reviewprocess we have been discussing, to ensure that the NDR addressed the Land Question taking into account all the considerations we have listed above in the propositions numbered (i) to (xxiii).

XVIV

The matter of whether the land required to address all the objectives indicated immediately above is acquired through expropriation without compensation, or otherwise, is entirely an operational or tactical question and should not be elevated into a strategic issue.

With regard to agricultural land, bearing in mind all the foregoing, we argue that the ANC must return to its historic positions according to which it dealt with the Land and National Questions as an integrated whole, therefore ensuring that at all times they are considered together within one process.

Accordingly, with regard to the immediate foregoing, it is absolutely imperative that the ANC confirms, unequivocally, that it remains firmly committed to the view expressed in the Freedom Charter that – The Land Shall be Shared Among Those Who Work It!

Equally, it must reaffirm its determination to address the objectives stated under the call in the Freedom Charter expressed as – There Shall be Houses, Security and Comfort!

One of the strategically important results of the confirmation of attachment to these Freedom Charter positions by the ANC would be that the ANC would walk away from the very unfortunate claim it has made, reflecting the ‘narrow, racialistic and chauvinistic African nationalism’ which Duma Nokwe, on behalf of the ANC, denounced in 1958, that it supports land expropriation without compensation because it must correct an historical injustice, thus to punish the descendants of the European Settler populations of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and theoretically reward those who were disadvantaged by these Settler populations!

There can be no doubt that more land should be made available to the black majority in our country, for various purposes.

Equally, there is no doubt that to achieve this objective, the democratic State must have the possibility to expropriate land without compensation in the public interest.

That public interest obviously includes redressing the imbalances of the past, as specifically provided for in our Constitution.

Accordingly we strongly assert that all the controversy about the principle and practice of land expropriation without compensation has been misplaced because even our Constitution allows for this to happen, and has authorised the approval of legislation which would make this possible through approved Statutes.

The principle and strategic matter at issue is therefore not about the manner of acquisition of land to address the Land Question in the context of the NDR.

Rather, the matter at issue is and has been how our country should properly address the Land Question, bearing in mind the simultaneous challenge also to address the National Question.

The question is what should be done to acquire the required land without communicating a wrong principle that such Land acquisition is being conducted because sections of our population must surrender land they own to others who are allegedly properly South African, whereas such land owners are, in effect, not accepted by Government as being fully South African, enjoying equal rights with all other South Africans, black and white?

XV

Before we conclude, there is one other important strategic matter we must address.

This is that essentially ours is a capitalist economy, which largely operates as any other capitalist economy does.

However, despite what we have just said, the fact is that capitalism in our country has “South African characteristics”, to borrow a Chinese expression.

It is perfectly obvious that for any democratic Government in our country successfully to lead a process which in the immediate and medium term, among others, leads to:

- sustained high economic growth;

- a significant reduction in wealth and income inequality; and,

- meaningful progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals;

it would have to take very serious steps to mediate the impact of capitalism “with South African characteristics” on the major strategic structural objectives our country must pursue to achieve the goal of “providing a better life for all”, a goal which the ANC has presented to our electorate since 1994.

What we are proposing would not be easy.

This is because the entire capitalist system both domestically and globally would resist any attempt to regulate its operation, beyond what our country is already doing.

The fact, however, is that no major socio-economic objectives pursued by our Government can be achieved without the active and conscious cooperation of the private owners of capital!

Accordingly whatever our Government does to implement the Resolution on the Land Question as adopted at the ANC 54th National Conference, including meeting its attached conditions, requires the conscious involvement and support of private capital.

So far, unfortunately, the ANC has said very little about what it will do to get private capital to cooperate in the process to ensure the success of the Government’s Land Policy, even as stated by the 54th ANC National Conference.

XVI

The ANC must fully discharge its responsibilities on the Land Question as our country’s Governing Party.

In this regard it must explain in public and in detail what it intends to do relating to all major issues relating to the Land.

In this context it must explain the relationship of its Land Policy relative to the National Question in our county.

All the preceding means that the Government must put in place a credible, affordable and detailed Programme of Action (PoA) on the Land Question to encourage popular ownership of this PoA.

Such PoA must be integrated with the perspective which seeks to ensure that the spatial differences with regard to Land use are resolved so as to accelerate the process towards the deracialisation of our system of human settlements, especially in our urban areas!

XVII

All genuine members and supporters of the ANC must understand that whatever their interpretation of what was decided at the ANC 54th National Conference, and what has happened since, correctly to represent the historic ANC Policies they must hold firmly to the view that:

- all decisions of the ANC about the Land Question must respond simultaneously to the National Question, with these considered together;

- whatever decisions the ANC takes must never negate the historical responsibility of the ANC to unite the people of South Africa to build a common non-racial society, as well as address the grievances of those who were disadvantaged by the systems of colonialism and apartheid;

- whatever the decisions on the Land Question, the ANC members must create the necessary space for everybody to understand that in reality the matter of access to the Land must be addressed and resolved in the context of rational agricultural and human settlement policies and programmes, focused on achieving a better life for all our people on a sustainable basis. [This is not a process equivalent to the important challenge to bring a just resolution to the injustice of the forced displacement and exile of the Palestinian refugees!]

Surely the debate on the Land Question has served to underline the imperative that the ANC has the historic responsibility to lead the complex process towards the achievement of the objectives of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR)!

That leadership role cannot be discharged by an ad-hoc and fragmented response to the tasks and challenges of the NDR.

At all times, as was the case in the past, the ANC must exercise its leadership understanding that it has to deal with a dialectically interconnected and complex social reality. This demands a comprehensive rather than a fragmented approach to the pursuit of the goals of the NDR.

That, in any case, is what characterises all truly revolutionary political formations!

ends

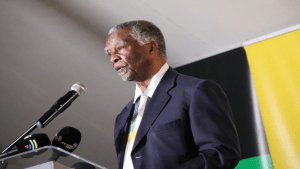

This article was first published in the Thabo Mbeki Foundation website.