China has drafted new rules to supervise biotechnology research, with fines and bans against rogue scientists after a Chinese researcher caused a global outcry by claiming that he gene-edited babies. The announcement comes as He Jiankui’s controversial experiment continues to transfix the scientific community, with researchers saying the procedure had the potential of enhancing the learning capabilities and memory of the babies.

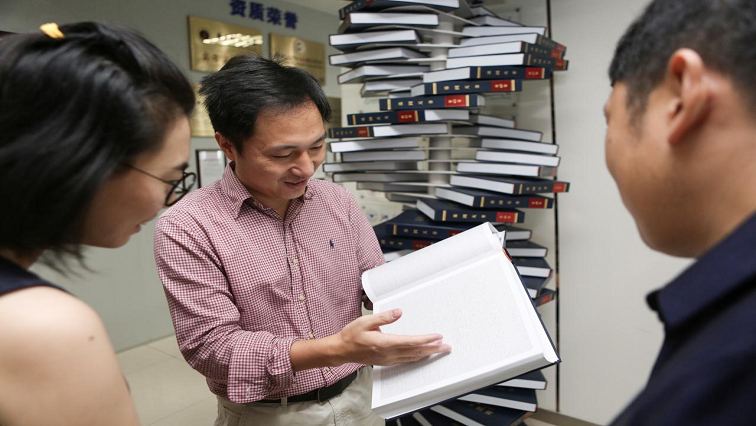

Jiankui announced in November 2018 that the world’s first gene-edited babies, twin girls, were born that same month after he altered their DNA to prevent them from contracting HIV by deleting a certain gene under a technique known as CRISPR. The claim shocked scientists worldwide, raising questions about bioethics and putting a spotlight on China’s lax oversight of scientific research.

Gene-editing for reproductive purposes is illegal in most countries. China’s health ministry issued regulations in 2003 prohibiting gene-editing of human embryos, though the procedure is allowed for “non-reproductive purposes.”

The new rules, unveiled by Beijing on Tuesday, propose to classify technology used for extracting genetic materials, gene editing, gene transfer and stem cell research as “high risk.” Health authorities under the central government would manage such research. The State Council, China’s cabinet, would be responsible for “the supervision and administration of clinical research and applications throughout the country,” according to the rules.

The new draft proposes fines of between 50 000 and 100 000 yuan ($7 500 and $15 000) for scientists or institutions that carry out research without proper authorisation, and the government can stop the work. Scientists can also be fined ten to 20 times the amount of “illegal income” earned from unauthorised research and be banned from their field of work for six months to one year.

“If the circumstances are serious, their medical practice licence shall be revoked and the individual shall not engage in clinical research for life,” the rules say.

Jiankui has been placed under police investigation, the government ordered a halt to his research work and he was fired by his Chinese university. His experiment involved deleting a gene called CCR5, a process that could also enhance memory and the brain’s ability to make new connections, linking it to academic success, according to a study published in the journal Cell.

“Certain aspects of cognitive function, including long term memory, could have been enhanced by the CCR5 mutation in the twin girls,” said Alcino Silva, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

His team first discovered how the CCR5 gene affected learning and memory in mice in 2016. The study by Silva and others showed people who naturally lack the CCR5 gene recover more quickly from strokes. People missing at least one copy of the gene also seem to have better learning abilities, it said, suggesting a possible role in everyday intelligence.

“It is very possible that other aspects of cognitive function (of the twins) may have also been disrupted. We simply do not know enough at this time to be altering the genome of healthy babies…There was no reason to put these two babies through an untested and potentially very dangerous, life-altering procedure,” Silva said.

Eight volunteer couples, HIV-positive fathers and HIV-negative mothers, signed up for Jiankui’s trial. A second woman became pregnant in the experiment, but it is unknown if she has given birth yet.

Miou Zhou, a professor at the Western University of Health Sciences in California, told AFP he was “shocked” by the controversial experiment, which could inflame speculation about the creation of super-intelligent humans using gene-editing technology.

“Because I have been studying CCR5 on cognitive function in mice for a long time, I remember my first reaction was why (did) he choose CCR5 to make the first genetically edited babies?” Zhou said.

During a human genome summit in Hong Kong in 2018, Jiankui acknowledged he knew about the potential brain effects of tinkering with the CCR5 gene from Silva’s and Zhou’s previous research dating back to 2016.

“I saw…(Silva’s) paper, it needs more independent verification,” he replied when asked about it during a Q&A session. “I am against using genome editing for enhancement.”

Investigators told Xinhua that He was “pursuing personal fame” and used “self-raised funds” for the experiment; but a November submission by Jiankui’s team to the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry has identified the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Free Exploration Project, a publicly-funded programme overseen by the local government, as bankrolling the experiment.

The programme, however, denies funding Jiankui’s project. A statement on its official WeChat social media account said it “never sponsored” Jiankui’s experiments and that the information provided to the clinical trial registry “was not true.”