Today marks 28 years since the Boipatong massacre, which some say was a watershed moment in South Africa’s negotiated transition.

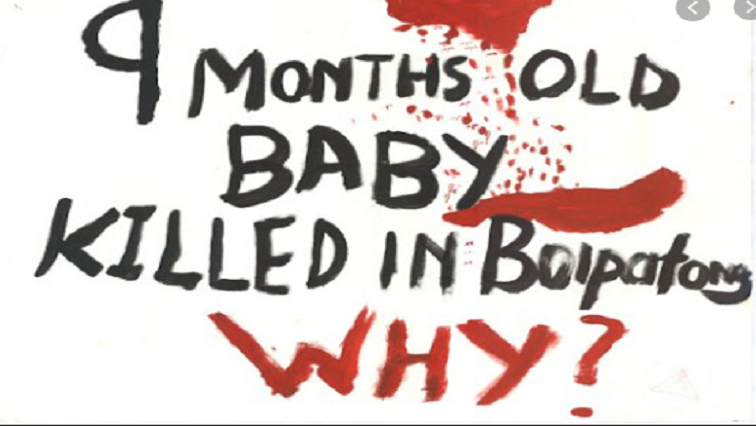

On the night of 17 June 1992, simmering tensions between the residents of Boipatong and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) supporters boiled over and armed hostel dwellers pounced on unsuspecting locals, stabbing, shooting and hacking at least 45 of them to death.

A four-month old infant, a four-year-old child and a pregnant woman were among the victims of the onslaught.

TODAY IS THE 28TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BOIPATONG MASSACRE.

The #BoipatongMassacre reflects the pain of transition and the difficult decisions we need to make. It also educates us never to get derailed no matter the pain and challenges.#GautengCares pic.twitter.com/jvp0P76LXc

— Gauteng Dept. of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation (@GautengSACR) June 17, 2020

The assailants were from the KwaMadala Hostel and were suspected to have collaborated with the apartheid police.

During the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) amnesty hearing in Vanderbijlpark in 1999, 16 men who had been convicted for the massacre rejected claims of the police’s nor high ranking IFP members’ involvement.

This despite a testimony by a former ANC supporter, who had defected to the IFP two years before the massacre.

So many unanswered questions to this event. Who were the instigators? Remember #BoipatongMassacre pic.twitter.com/iaKiYIPhBz

— Dumani Nonke Mbebe????? (@panafricanist90) June 17, 2020

He had accused the late IFP Gauteng leader Themba Khoza and a former police sergeant, Pedro Peens of involvement.

British criminologist Dr. Peter A.J. Waddington, who was tasked to probe the attack, found that while police had done a shoddy job in investigating the massacre, there was no evidence of police complicity or involvement in the massacre. According to South African History Online, Waddington concluded that the South African Police (SAP) lacked proper investigative procedures in dealing with sensitive cases such as the massacre.

#Boipatong #BoipatongMassacre #RememberBoipatong

17 June 1992.

‘Jane clutched her child, looking at the men in the eye, and then watched as an assegai was driven through the little girl’s body.

They stabbed Jane too, and chopped her fingers off.’ pic.twitter.com/TxkCQ2hzJ9

— Tumi Sole (@tumisole) June 17, 2020

The incident sparked public outcry, with ANC members responding by burning the homes of police and IFP members.

It also came during a deadlock of South Africa’s CODESA talks, which were meant to chart a way for a new democratic society. The ANC withdrew from the talks in protest, but the negotiations were later revived, leading to elections two years later.

The people of Boipatong barred FW de Klerk from entering the township. How could his ‘government’ & its IFP sympathisers kill them & then later come & commiserate with them? This iconic image was taken by Greg Marinovich. #BoipatongMassacre #NeverForget pic.twitter.com/31pbuTxnDM

— Qhoboshendlini (@LoyisoSidimba) June 17, 2019

In the Voices of Boipatong, Historian and Researcher James Simpson says: “Boipatong’s people were not a passive audience. Their anger with police was manifest hours before their leaders sought to rouse it. Whether or not the accusations they levelled were true, their call for change reverberated across the country, through the authoring of testimonies, the stamping of feet, the singing of songs, and throwing of stones. South Africa and the world stopped to listen.”

Simpson says it was the people’s anger that forced then President F.W de Klerk to finally give in to a future of majority rule.

“Ensuing struggles over the meaning of Boipatong saw the gap it had opened expand ominously into a darkening chasm, threatening to force the pieces of South Africa’s torn landscape further and irrevocably apart. It was de Klerk who chose to relent. The swirling mass anger that animated the abyss was aimed at him and his government, as was the brunt of international reproach. Before Boipatong, he had fought tenaciously to retain minority powers, all the while seeking majority support. After the massacre, he resigned himself to the new role of benefactor to the ANC’s inevitable rise. The National Party would no longer pursue the retention of power through collaboration with the Inkatha Freedom Party, nor would it stand idly by as violence continued unabated.”

South Africans on social media are paying homage to those who lost their lives to the bloodshed.

Boipatong Massacre: Another heavy reminder of SA?? painful past. Have we done enough for the victims of that horrible night? The perpetrators were forgiven but mothers and children were left widowed, some killed and others paralyzed. #DailyThetha #BoipatongMassacre pic.twitter.com/52SH3ZKcLY

— Nicolette Mashile (@ImcocoMash) June 17, 2020

Today we commemorate the #BoipatongMassacre that took place on the night of 17 June 1992.

By the grace of God, my family survived the night of this horrid act against humanity.

Lives were lost. Families ripped apart. My community was left in shambles. Lest we forget. pic.twitter.com/JZyjOTLMN9

— Maggie (@MagdelineMaepa) June 17, 2020

#BoipatongMassacre#VaalTwitter

Today marks 28 years since the massacre took place in 1992, where 45 people were killed✊? pic.twitter.com/J83PkoPAHT— fikile (@melbabem) June 17, 2020

These memories are still raw, yet mainstream history is written to forget. #NeverForget #BoipatongMassacre #RememberBoipatong https://t.co/qHId5KbzNa

— Joy-Tendai? (@JoyTendai) June 17, 2020