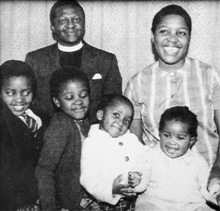

Early life Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in Klerksdorp on 7 October 1931 and schooled in Ventersdorp, Krugersdorp and Johannesburg. His father was a primary school principal and his mother worked as a cleaner and a cook at a school for the blind. Tutu recalls that as a child, one day he saw a white priest raise his hat to his mother. He had never seen a white man pay this courtesy to black woman and the gesture made an impression on him. The priest was Trevor Huddleston, who was to play a significant role in Tutu’s life. By 1954 Tutu had a teaching diploma from the Pretoria Bantu Normal College and he later a completed a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Africa (UNISA). But after three years as a teacher, Tutu quit in protest against the deteriorating standard of Black education that resulted from the implementation of the Bantu Education Act of 1953. Academia, early struggle, family – 1955 to 1975 On 2 July 1955, Tutu married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a teacher who was taught by his father. They had four children: Trevor Armstrong Thamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Ursula Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Andrea Tutu, all of whom attended the Waterford Kamhlaba School in Swaziland. The Tutus have been married for more than 50 years. Having left teaching, Tutu enrolled at St Peter’s Theological College. He was ordained as a deacon in 1960, and became a priest in 1961. In 1962 he moved to London, where he completed his Honours and Masters degrees in Theology in 1966. Tutu then returned to South Africa and taught at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice in the Eastern Cape. In 1970 he was offered a lecturing position at Roma University in Lesotho. He was appointed Associate Director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches in Kent, London in 1972. He returned to South Africa in 1975 to take up the post of Anglican Dean of Johannesburg. Soweto uprising and beyond Between 1976 and 1978 Tutu was the Bishop of the Anglican Church in Lesotho and the General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches. In 1976, protests in Soweto over the Apartheid government’s enforcement of Afrikaans as a compulsory medium of instruction in black schools culminated in the massacre of dozens of students, which triggered widespread unrest and world outrage. Tutu had become increasingly outspoken about Apartheid and the privations suffered by blacks. Although his criticism was unflinching, he constantly urged reconciliation between all sides. Like many who spoke out against Apartheid, he was harassed by the state security police and his passport was confiscated. During this time a number of South African activists were “banned,” with stringent conditions which entailed constant surveillance and prevented them from communicating with others or travelling freely. Mamphela Ramphele, who was banished to a remote rural area, recalls that Tutu undertook to telephone her once a week and comfort her. He kept his promise week after week, despite difficult circumstances for them both and it became a source of great encouragement to Ramphele. A number of South Africans have spoken about Tutu’s humanity during those very trying times. The 1980s Desmond Tutu continued to speak out against the injustice of Apartheid and in 1984 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, the first South African to receive the accolade since Albert Luthuli in 1961. In 1985, he was appointed the Bishop of Johannesburg and a year later became the first black cleric to lead the Anglican Church in South Africa when he was named Archbishop of Cape Town. From 1987 to 1997 he served as president of the All Africa Conference of Churches. Archbishop Tutu urged foreign disinvestment in South Africa as a way to pressurise the government to dismantle Apartheid, and was the focus of harassment by the security police as a result. Like murdered activist Steve Biko, he also urged civil disobedience. It led to events such as the “purple rain” protest in Cape Town in 1989, where protesters were sprayed with purple dye to identify them to the police for arrest later.

President Mandela asked Archbishop Tutu to chair the TRC, with Dr Alex Boraine as deputy chairman

The 1990s Following his appointment in 1989 as State President, FW de Klerk on 2 February 1990 unbanned the ANC and other political parties, and announced plans to release Nelson Mandela from prison, which took place on 11 February. The process was not without violence: 19 April 1993, Chris Hani, leader of the SACP, was murdered by right-wingers. At Hani’s emotionally-charged funeral, Archbishop Tutu urged the crowd of around 120 000 to work peacefully together and end apartheid. He called on the mourners to chant with him: “We will be free!”, “All of us!”, “Black and white together!” Archbishop Tutu told the throng: “We are the rainbow people of God! We are unstoppable! Nobody can stop us on our march to victory! No one, no guns, nothing! Nothing will stop us, for we are moving to freedom! We are moving to freedom and nobody can stop us! For God is on our side!” Following the democratic elections in 1994, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was set up to bear witness to, record and in some cases, grant amnesty to the perpetrators of crimes relating to human rights violations. President Mandela asked Archbishop Tutu to chair the TRC, with Dr Alex Boraine as deputy chairman. Public hearings of the Human Rights Violations Committee and the Amnesty Committee were held at a number of venues around South Africa. The hearings were often harrowing and emotional, conveying the toll that Apartheid took on all sides of the liberation struggle. On October 28, 1998 the Commission presented its report, which condemned both sides for their atrocities. The TRC has become a model for a number of similar post-conflict procedures around the world. When Archbishop Tutu retired in 1996, Nelson Mandela told a dinner to honour him: “His joy in our diversity and his spirit of forgiveness are as much part of his immeasurable contribution to our nation as his passion for justice and his solidarity with the poor.” Widely described as “South Africa’s moral conscience,” Archbishop Tutu continues to campaign vigorously for human rights throughout the world, speaking out on a variety of issues such as: The plight of Zimbabweans under the regime of Robert Mugabe: “We Africans should hang our heads in shame. How can what is happening in Zimbabwe elicit hardly a word of concern let alone condemnation from us leaders of Africa? After the horrible things done to hapless people in Harare… what more has to happen before we who are leaders, religious and political, of our mother Africa are moved to cry out “Enough is enough?”The lack of progress on treating HIV/AIDs in South Africa: “Those of you who work to care for people suffering from AIDS and TB are wiping a tear from God’s eye.”The treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli government: “My heart aches. I say, why are our memories so short. Have our Jewish sisters and brothers forgotten their humiliation? Have they forgotten the collective punishment, the home demolitions, in their own history so soon? Have they turned their backs on their profound and noble religious traditions? Have they forgotten that God cares deeply about the downtrodden?” The Elders In 2007 Archbishop Tutu, Nelson Mandela and Graça Machel convened The Elders, a group of world leaders who contribute their integrity and leadership in dealing with some of the world’s most pressing problems. Other members include Kofi Annan, Ela Bhatt, Gro Harlem Brundtland, Jimmy Carter, Mary Robinson, Muhammad Yunus and Aung San Suu Kyi, whose chair was left symbolically empty due to her continued confinement by the military junta in Burma. Archbishop Tutu is Chairman of the Elders and continues to work energetically in a number areas of human-rights and his ministry.

– By Tutu Centre of Peace