This week marks 25 years since the man credited with taking down the foundation of apartheid was transferred from the Pretoria Central Prison to a mental institution.

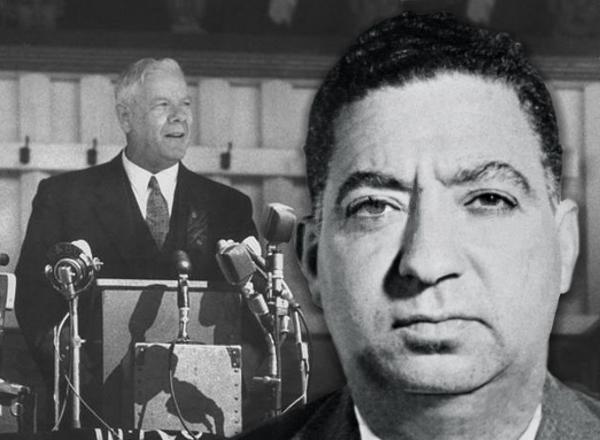

Dimitri Tsafendas, a temporary Parliament messenger, killed the so-called architect of state racism Dr Hendrik Verwoerd in cold blood on the floor of the then House of Assembly on 06 September 1966. He had followed him into the debating chamber; where he was due to make a speech.

He pulled out a sheaf knife and plunged it into his heart and lungs four times.

Pandemonium broke and Tsafendas was restrained after being punched in the face.

The Prime Minister died within minutes from his wounds, which some believe could only have been made with training.

In a statement to the police six days after the assassination, Tsafendas admitted to the murder, saying he was disgusted by apartheid.

“I did not care about the consequences for what would happen to me afterwards. I was so disgusted with the racial policy that I went through with my plans to kill the Prime Minister.”

A point he repeated during a documentary on his life 21 years ago.

“Dr Hendrik Verwoerd was an immoral man. I decided to stab him and kill him,” he said.

According to SA History, it was after the gunning down of unarmed peaceful anti-pass law protesters in the 1960 Sharpeville massacre when he decided to take violent action against the apartheid regime.

He had previously wanted to kidnap the man who was once described as having seen Black people as a problem he couldn’t solve.

Truth or conspiracy theory

In a documentary on his life, Tsafendas’ friend and church mate Patrick O’Ryan paints a story of frustration, heartache and injustice that drove a decent man to such a horrific act.

O’Ryan says Tsafendas once expressed disgust for Verwoerd, saying he’d bash his skull should he ever get hold of him.

However, he says these are the facts he never disclosed to authorities during the inquiry into the killing.

Instead, he says, they went along with the cover-up worm story that investigators asked them to give as an account while testifying to get Tsafendas off the death row.

Tsafendas had, after all, been hospitalised for a tapeworm delusion at Grafton State Hospital, Massachusetts, in 1946, and again in Hamburg, in 1955. After the assassination, at least six psychiatrists confirmed his diagnosis of schizophrenia and/or delusion.

More than what meets the eye

While some still believe the killing was an act of mindlessness – others suspect the murder was well planned. They cite his detachment to the gravity of his deeds as reason enough to believe Tsafendas was trained to kill Verwoerd.

Right wing extremists have suspiciously pointed the missile to then Police Minister John Vorster, whom they believe appeared too calm when the knife was plunged into Verwoerd’s body.

The psychiatrist who treated him and David Pratt, the man who had shot Verwoerd six years before the assassination, is another suspect.

He apparently treated both men in 1959 and was present at the Rand Show during an attempt on Verwoerd’s life in 1960.

Unsung hero?

Writer and former political prisoner Breyten Breytenbach has described Tsafendas and struggle icon Nelson Mandela as two sides of the same coin.

“The one of companions and because of the fact that he could hold on to the belief of the justice that he had done. The one could transform the whole 27 years into a building block for what comes later. The other one left a shadow part of that experience. Deprived of all objectivity and deprived of any form of self-justification,” Breytenbach told filmmaker, Liza Key.

In her thesis, Dr Zuleiga Adams says Verwoerd’s assassination exposed the fault lines of apartheid governance.

“Tsafendas’ life story had, as we shall see, defied the rules of racial rationalism upon which the apartheid state was based. He had crisscrossed South African and international borders with seeming impunity. His personal genealogy was the very antithesis of a system where racial laws were tightly designed to eliminate frontier zones between white and black. His very presence in South Africa attested to the failure of an immigration regime to keep out ‘half-castes’, ‘communists’, and the ‘mentally disturbed’, as he was variously referred to in official documentation.”

The author of a book on Tsafendas, The Man who killed Apartheid, Harris Dousemetzi has petitioned government to correct history books on Tsafendas.

He wants Tsafendas to go down in history as a sane man who had killed Verwoerd with the hope that apartheid would collapse.

Dousemetzi’s call has the blessing of some of the country’s great legal minds, including Human Rights Lawyer George Bizos, former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza as well as retired Constitutional Court Justice Zak Yacoob.

Life in Prison

A three-day inquiry into the murder was conducted and on 20 October 1966, Tsafendas was declared unfit to stand trial – getting him off the murder charge.

Judge Andries Beyers committed him as a state President’s patient, creating an expectation that he would be held in a mental hospital.

However, instead of keeping him at a psychiatric hospital as expected, it placed him on death row after exploiting a loophole in the law.

He was held for four months on Robben Island and was later placed on death row in the Pretoria Central Prison, in a cell specially designed for him where he was punished daily for his deed for at least 23 years.

The cell was within an earshot of the execution chamber; he could hear prisoners when they were being taken for their last journey of life; hear them breathing; their cries and the silence that follows their hanging.

In the mornings, he used to wake up and see them hanging.

Tsafendas has said warders used to put a strait jacket on him and punched him until he was unconscious.

They also threw out his food, wet his bed with water and sometimes even threw it on the floor and asked him to clean it up.

Tsafendas was transferred to Zonderwater Prison in 1989.

Last days

On 30 June 1994, Correctional Services Minister Dr Sipho Mzimela announced that he would be moved to Sterkfontein Psychiatric Hospital, where he spent most of his remaining days on earth.

Government reportedly wanted to release him from custody, but couldn’t find any family or friends who could accommodate him at the time.

Tsafendas died a lonely man, in 1999 from pneumonia.

He was buried in an unmarked grave, something that doesn’t sit well with former ANC Eastern Cape Provincial Member of Parliament, Christian Martins.

Martins believes Tsafendas shouldn’t go down in history as a deranged man, but a man who played a part in liberating Black people from the National Party’s oppressive racial policies.

In 2013, he applied for Tsafendas and Verwoerd’s graves to be declared national heritage sites.

He believes their story is not one to be swept under the carpet, adding that had Verwoerd lived longer the holocaust was going to be a child’s play compared to the devastating impact the policies that he advocated for and had effectively developed could have had.

Changing the course of history

Tsafendas was 48 years old when he made history, sending the Afrikaner world into mourning and exhilarating those who either disagreed or were on the receiving end of the brutal apartheid laws.

He managed to carry out an act wealthy businessman and farmer, David Pratt had tried six years earlier against a man he called the epitome of apartheid.

Pratt shot Verwoerd twice on the face at close range in 1960 during an event in Johannesburg. He later told authorities that he had not wanted to kill him but had hoped the incident could give him time to re-think his government’s policies.

The assassination attempt happened 19 days after the Sharpeville massacre, a tragedy that reportedly also got Tsafendas hopping mad.