Can the BRICS Africa Outreach agenda elevate BRICS’ relations with the African continent to a new level of cooperation?

Widely touted as a major milestone in the developing relationship between South Africa and its BRICS partners, the message at the 10thannual BRICS summit in Johannesburg last month is resoundingly clear: Both BRICS and South Africa, in particular have a strong desire to deepen mutually beneficial, pragmatic cooperation in the African continent.

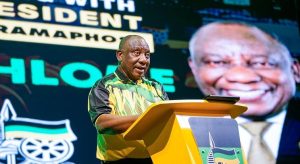

South Africa, under the leadership of President Cyril Ramaphosa, hosted the 10th BRICS Summit under the overall arching theme “BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4th Industrial Revolution”.

The leaders of the five nations met at a time the US was threatening to impose trade tariffs against other countries that are likely to derail global growth.

This gave the BRICS leaders an opportunity to showcase the importance of multilateralism. At the conclusion of summit, the BRICS leaders adopted the Johannesburg declaration, which reaffirms principles of mutual respect, sovereign equality, democracy, inclusiveness and strengthened collaboration.

In addition, the following areas of cooperation were agreed upon:

- Establishment of the BRICS Energy Research Cooperation Platform

- Establishment of the BRICS Networks of Science Parks, Technology Business Incubators and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

- Commissioning of the review of the BRICS Joint Trade Study on promoting intra-BRICS Value Added Trade

- Establishment of a BRICS Working Group on Tourism

With trade protectionism growing in popularity, the BRICS nations can harness on each other to increase mutually beneficial intra-trade flows. The inclusion of Africa through the BRICS-Africa Outreach program as well as the inclusion of other emerging economies through the BRICS Plus Initiative provides a platform to partner with a wider community to grow trade.

The biggest challenge the bloc is likely to face is up-skilling the current workforce to benefit from the opportunity provided by the 4th industrial revolution. Without active steps to get this right, leapfrogging to development may be a distant dream.

The summit also enabled South Africa to showcase to the rest of the world that it is open for business. In pre-meeting engagements, President Cyril Ramaphosa was able to secure $14.7bn investment in investment commitment from China. Ramaphosa has made significant progress in his $100bn investment drive, receiving commitments from the UK (US$64m), Saudi Arabia ($10bn) and the UAE (US$10bn). Mercedez Benz earlier in the year also announced that it will be investing R10bn.

These commitments, once realised, will provide the much-needed boost to the local economy.

Five years since the 2013 eThekwini Summit when South Africa initiated the BRICS-Africa Leaders Dialogue Forum Retreat, attended by 12 African leaders representing the African Union (AU), the New African Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad) and the eight AU Regional Economic Communities (RECs), the BRICS-Africa nexus had a curious ring of reassurance in the discussions on implementing the Outreach programme.

Beneath this welcome news, however, lie some deep uncertainties about the future of Africa’s trade relations with BRICS. Emboldened by an escalating trade war, evidenced by rising tariff barriers in the United States (US), the protracted and seemingly complex withdrawal of Britain from the European Union (EU) under Brexit, BRICS Outreach’ seems a natural reflex by African countries. Yet, fermenting, too, has been a pervasive climate of scepticism in some quarters of the African continent towards BRICS generally, and China in particular. While it is true that friendship and cooperation, which underpin the BRICS partnership framework, comes from equality, can the BRICS Outreach programme be a genuine vehicle for mutual cooperation?

Short end of the stick

Since South Africa’s inclusion in BRICS in 2011, there have been mounting concerns that African economies are getting the short end of the stick. While BRICS has presented itself as an alternative to the economic prescriptions of the Bretton Woods institutions, the flip side of this policy avowal are allegations that South Africa has merely courted Chinese ‘neo-colonialism’ on the continent, representing an asymmetrical relationship that resembles the classic north-south model of exporting raw materials while importing manufactured goods – a model critics say BRICS ostensibly embeds in its trade relations.

At first, this may appear to be the case – certainly at the level of trade data. As Africa’s largest BRICS trading partner, some 1500 Chinese companies have invested in African countries in the last two decades, mostly on the back of Chinese-sponsored development projects and infrastructural support for its extractive interests. On the African export side, one could argue that much of the revenue generated has been a result of rising oil and commodity prices rather than growth in actual trade volumes. An observation is that deficits on the African side abound, including in South Africa, Chinese foreign direct investment into South Africa, for instance, has been scant. The chink in the chain – and a cardinal lesson for South Africa and the rest of the continent – lies in the overriding question: will the anticipated growth in trade volumes between BRICS countries and Africa increase or decrease Africa’s trade deficit?

Let’s start with statistics.

Combined and uneven development

Collectively, BRICS countries have a GDP of USD$ 18.5 trillion, or 22.8 % of the share of global GDP, according to the BRICS 2018 annual report. Despite the geographic distance between some BRICS countries, the combined value of intra-BRICS trade is estimated at USD$ 242 billion.

However, this broadly bristling picture masks a more complex story. As the current-year performance, along with the longer-term forecasts in the BRICS 2018 Annual Report, suggests, the five member-countries are expanding at very different rates. In 2016-2017, the share of industrial output in GDP of China, Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa accounted for 39.8%, 21.2%, 32.4%, 28.8% and 28.9%, respectively, according to the 2018 BRICS Annual Report. The distribution of manufacturing’s share across the BRICS countries is skewed towards China (73%), with Brazil, Russia and South Africa net commodity exporters and India a primarily service-based economy.

In broad terms, the growth trajectories are a result of two drivers within the BRICS grouping — those economies that took advantage of globalisation’s march to integrate themselves into global supply chains (primarily China and India) and those that took advantage of globalisation to sell their abundant natural resources (primarily Brazil, Russia and South Africa).

As BRICS’ exports are likely to be blocked by rising US tariffs, all this points to industrial powers such as China and India in the direction of Africa, according to the BRICS Annual report. Overlooked, however, are the potential long-term benefits for Africa’s manufacturing sector. Although the return to growth for Brazil, Russia and South Africa last year has had much to do with a recovery in world commodity prices during 2016-2017 – whereas China and India have been buoyed by strengthening demand for manufacturing and services exports – the challenge facing South Africa and the African continent relative to BRICS can in part be attributed to development patterns that unfortunately do not accurately reflect the true potential for mutually beneficial cooperation.

Diversification – the challenge

The Outreach policy is, in one sense, emblematic of a broader re-examination within the BRICS bloc of the growth story. At the same time, the initiative underscores the need for policymakers in both BRICS and African economies to shift their focus towards sustainable and inclusive growth paths in the longer term. While only a narrow base of countries is benefitting from China’s commodity hunger, it nevertheless poses questions as to whether African economies can optimise the opportunities presented by the initiative to diversify their economies towards manufacturing activities with strong multiplier effects for small business development and employment creation.

Against a recent backdrop of firming recoveries in advanced economies to pre-2008 crisis levels, the 10th BRICS summit correctly noted that monetary and fiscal policy levers have become less of a priority, and productivity-enhancing structural reforms have become increasingly urgent as the pressures of technological disruptions and the 4th Industrial Revolution on business and labour intensify.

“African economies therefore face the challenge of diversifying their exports away from unprocessed commodities and raw agricultural products; improving education and health systems; boosting value-added exports; and implementing business climate reforms,” the summit declared.

In recognition of this, the BRICS Africa Outreach policy has identified development finance through the New Development Bank, infrastructure development, agro-business, human resources, skills training, disease prevention and treatment, and disaster relief, among other things, as areas of cooperation. All these efforts will be critical to a sustainable growth path, alleviating poverty and, if accompanied by a rising number of skilled workers, to reducing inequality. This may sound like the standard prescriptions of development economics. There’s a reason for that: structural reform and diversification are fundamental to sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Thulasizwe Mbele who is the Head of Strategy at BLSA writes in his personal capacity.